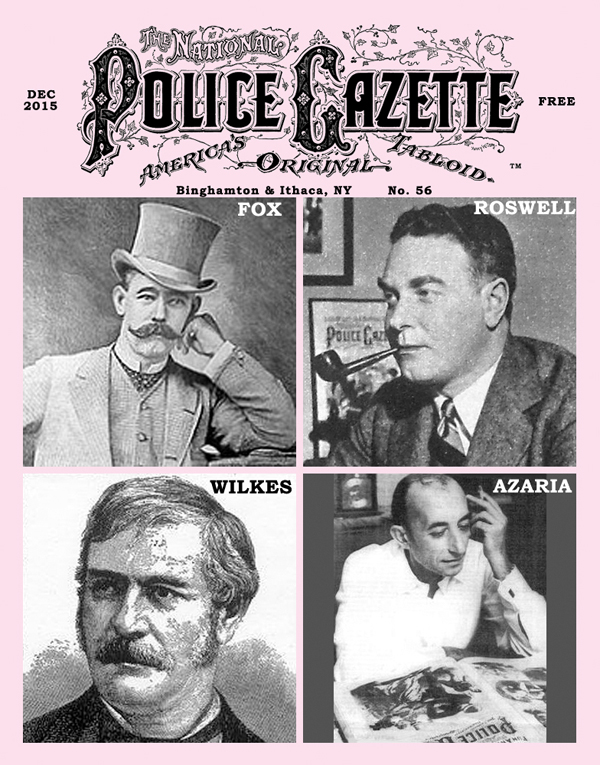

Pictured on this month’s cover are the four men most responsible for making and keeping the National Police Gazette an American institution for 130 years. All of them are pioneers and/or geniuses in the field of popular magazines, and all of them knew there was something about the Police Gazette in particular that made it worth the effort.

Of the four, it must be admitted the most significant, not only for the Police Gazette but for all of pop-culture publishing, is Richard K. Fox. An immigrant from northern Ireland, Fox took control of the Gazette in 1877 and immediately undertook to remake the weekly in his own sensationalistic image—not unlike what William M. Gaines would do decades later after taking over “Educational Comics” and having it produce Tales From The Crypt and Mad Magazine. Fox not only perfected sensational/tabloid journalism but made the Gazette the forerunner of the illustrated sports weekly, the girlie/pin-up magazine, the celebrity gossip column, the men’s lifestyle magazine, and Colbert Report/Howard Stern-style ironic coverage of current events. He also had a blast being the Guinness World Records of his day. The trophies, medals and prizes handed out by the Police Gazette for achievements in every activity imaginable numbered into the thousands. The Gazette even sponsored Harbo and Samuelsen, the first people ever to row a boat across an ocean, partly because other publications—thinking the attempt too dangerous—refused to do so. Even with all these credits under his belt, Fox’s greatest impact may have been on the sport of boxing, which, when Fox took control of the Gazette, was illegal in every jurisdiction in the country and devoid of any regulatory authority. The Police Gazette changed all that. Fox’s tireless promotion and management of the sport raised it to a level of respectability and popularity it would never fully relinquish. Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst would later apply Fox’s innovations to the daily-newspaper format and the rest, as they say, is history.

If Richard K. Fox made the National Police Gazette a spectacular 19th-century phenomenon, then Harold Roswell is the reason it became one in the 20th century. Roswell, with partner Edward Eagle picked up the Gazette at perhaps its most vulnerable moment. Following a gradual loss of focus and the death of Fox in 1922, the Gazette succumbed to the Great Depression and declared bankruptcy in 1932. It was purchased for a song by a pulp-magazine group led by Harry Donenfeld and Merle Hersey that got right to work bringing back the kind of shock and sensation beloved by Fox. Graphic articles and pictures of horrifying crimes and bare-breasted women on the front cover said the Police Gazette was reclaiming its place as the magazine you would spend all day in the barbershop reading, but would never have a subscription at home. Sadly, though the content was up to snuff, the business-management side suffered, and only a year and a half later Donenfeld and partners could no longer continue. When Roswell and Eagle took control in 1935, they brought with them the much-needed business discipline, and the Gazette gradually came back to life. For 10 years it focused on the familiar sex and crime. But in the late 1940s, Roswell—now the sole head—pivoted to featuring color sports photos on the cover—years before the debut of Sports Illustrated—reclaiming the Gazette’s legacy as the preeminent illustrated sports journal. Throughout the 1950s, he would also expand the Gazette’s celebrity gossip and sensational commentary on current events. Back in all its outrageous glory, the late 1940s through early 1960s were a new high-water mark for the National Police Gazette. Its “Hitler Is Alive!” series alone was worth the price of admission. Through perseverance, sound business management, and a feel for the “Police Gazette attitude” Harold Roswell became the magazine’s most successful owner after Richard K. Fox.

No list of important Police Gazette owners would be complete without the man who started it all. George Wilkes, with business manager Enoch Camp, wanted to publish a weekly similar to the “Police Gazette” of London, England, which reported details about fugitives and criminals for the benefit of law enforcement officials as well as the general public. Wilkes’s new publication would be the 19th-century version of America’s Most Wanted with John Walsh. On September 13, 1845, the first issue of the National Police Gazette hit the streets. It didn’t take Wilkes long to figure out—as Walsh did with America’s Most Wanted—that readers were picking up the magazine as much for thrills and entertainment as for helping to capture criminals. Wilkes also knew that libel laws of the time protected him from any actions as long as what he published came directly from public court documents. So if someone in a court proceeding testified the craziest, most outlandish things about someone else, Wilkes could publish the transcript in the Gazette and not worry about being sued. He also discovered that a good public crusade against a perceived menace sold copies. The most famous of these became the campaign against abortion provider Madame Restell. The Police Gazette’s unrelenting harangue against Restell was so effective it helped lead to her arrest and conviction. (The Police Gazette under Richard Fox, of course, became less serious and would most likely have handled the Restell case with ironic humor rather than a campaign to bring her down.) After some good years and some less good years, Wilkes sold the Gazette to a former New York City police chief. Its most memorable coverage in the remaining pre-Fox years would be of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

At the other end of the Gazette’s run, when Harold Roswell decided to sell and retire in 1968, one of the founders of the modern tabloid felt he could not miss the opportunity to pick up the reigns of the publication that had started it all. Joseph Azaria founded a little magazine called Midnight in 1950s Montreal. You still see it every time you check out at the supermarket. Only now it’s called the Globe. Azaria became very successful, but he had a career plan all mapped out: he would make as much money as he could in a short time and then retire by the age of 39. As part of this plan, he sold his stake in Globe Communications to a partner. But then the National Police Gazette came up for sale, and he couldn’t resist. Azaria kept the Gazette going for another nine years, but his mind was elsewhere. The plan was to be retired—he spent much of his time in South Florida winning backgammon championships—and the level of commitment needed to make it in the competitive world of publishing just wasn’t there anymore. The Police Gazette invented just about everything you can think of in the world of entertainment journalism. But as soon as competitors saw the success the Gazette made of something, they raced to imitate. And by this time there were dozens of other publications putting more energy and resources into doing the things the Police Gazette had done first. Joseph Azaria followed his retirement plans, ending up in Costa Rica. And the last issue of the National Police Gazette came out January 1977, completely made up of “Hitler Is Alive!” reprints.

Today, Steven Westlake and his company National Police Gazette Enterprises, LLC, manage all things Police Gazette.