FROM THE MORGUE

Copyright 2012 by William A. Mays, Proprietor

Revolver shots were heard in the ship's last moments. The first report spread among the boats was that Captain Smith had ended his life with a bullet. Then it was said that a mate had shot a steward who tried to push his way upon a boat against orders. None of these tales have been verified, and many of the crew say the captain, without a preserver, leaped in at the last and went down, refusing a cook's offered aid.

The last of the boats, a collapsible, was launched too late to get away, and was overturned by the ship's sinking. Some of those in it—all, say some witnesses—found safety on a raft or were picked up by lifeboats.

In the Marconi tower, almost to the last, the loud click of the sending instrument was heard over the waters. Who was receiving the message, those in the boats did not know, and they would least of all had supposed that a Mediterranean ship in the distant South Atlantic track would be their rescuer.

As the screams in the water multiplied, another sound was heard, strong and clear at first, then fainter in the distance. It was the melody of the hymn "Nearer, My God, To Thee," played by the string orchestra in the dining saloon. Some of those on the water started to sing the words, but grew silent as they realized that for the men who played the music was a sacrament soon to be consummated by death. The serene strains of the hymn and the frantic cries of the dying blended in a symphony of sorrow.

Led by the green light, under the light of the stars, the boats drew away, and the bow, then the quarter, then the stacks and at last the stern of the marvel-ship of a few days before, passed beneath the waters. The great force of the ship's sinking was unaided by any violence of the elements, and the suction, not so great as had been feared, rocked but mildly the group of boats now a quarter of a mile distant from it.

Sixteen boats were in the forlorn procession which entered on the terrible hours of rowing, drifting and suspense. Women wept for lost husbands and sons. Sailors sobbed for the ship which had been their pride. Men choked back tears and sought to comfort the widowed. Perhaps, they said, other boats might have put off in another direction toward the last. They strove, though none too sure themselves, to convince the women of the certainty that a rescue ship would appear.

Early dawn brought no ship, but not long after 5 A.M. the Carpathia, far out of her path and making eighteen knots instead of her wonted fifteen, showed her single red and black smokestack upon the horizon. In the joy of that moment, the heaviest griefs were forgotten.

Soon afterward, Captain Rostrom and Chief Steward Hughes were welcoming the chilled and bedraggled arrivals over the Carpathia's side.

Terrible as were the San Francisco, Slocum and Iroquois disasters, they shrink to local events in comparison to this world-catastrophe.

The world's annals have provided few more intense and dramatic moments than when all that was left of the great company that sailed so gayly on the Titanic appeared on the Cunard pier. No hint of the story of their miseries and of their sufferings after the Titanic foundered had come from the sea. It was not known for certain whether some who had been given up for dead might appear miraculously on the gangplank. There were scores of people, among them men and women whose names are familiar the country over, who waited in the most intense suspense while the Cunarder with her sad cargo made her way slowly up the Hudson, passed the great ships in dock, whose flags showed dimly at half staff in the bars of river light. There were some of these who did not dare to give up all hope, who lingered still a prey to the most dreadful uncertainty, who refused to believe the cruel list of those that were saved and thought that there might all appear for them some loved face. But nearly all of these were disappointed and turned away with looks that no man who saw the arrival of the Carpathia will ever forget.

The tragedy of the Titanic was written on the faces of nearly all of her survivors. Some, it is true, who were saved with their families could not repress the joy and thankfulness that filled their hearts, but they were very few compared to the number of the rescued. These others bore the impress of their time of darkness when their people passed in an accident that seemed like an insane vision of the night. Their faces were swollen with weeping.

The unhappy company so marvelously torn from the grip of the sea was received solemnly and with remarkable quiet by the crowd which gathered near the Cunard piers and by the few hundreds that penetrated by right of relation or friendship or merciful business to the interior of the pier. There was no cheering, no upraising of voices in salute of the living, for the thought of the dead was in the minds of all onlookers. The depression of death was oppressive on the spirit of the waiting men and women. Those who found their gladdest hopes realized and looked through the press to make out the well-known faces of husbands and fathers and sisters and wives could not conceal their tremendous elation, their thankfulness that all suspense and disheartening conjecture was over. But they greeted their rescued ones quietly for the most part.

Simon Senecal, a merchant in Montreal, who was a passenger on the Carpathia, in telling of the Titanic disaster, said:

"After rescuing the boatloads of women we sighted a liferaft on which were about twenty-four persons. One-half of these were dead. One of the Carpathia boats went to the raft and took the live men off, leaving the dead. The water was thick with bodies. Why, the crew of the Carpathia in rescuing had trouble in avoiding the bodies as they floated about in the water.

"I know of seven bodies which were buried by the crew of the Carpathia after the rescue. If there were any other bodies buried I do not know."

The last of the boats, a collapsible, was launched too late to get away, and was overturned by the ship's sinking. Some of those in it—all, say some witnesses—found safety on a raft or were picked up by lifeboats.

In the Marconi tower, almost to the last, the loud click of the sending instrument was heard over the waters. Who was receiving the message, those in the boats did not know, and they would least of all had supposed that a Mediterranean ship in the distant South Atlantic track would be their rescuer.

As the screams in the water multiplied, another sound was heard, strong and clear at first, then fainter in the distance. It was the melody of the hymn "Nearer, My God, To Thee," played by the string orchestra in the dining saloon. Some of those on the water started to sing the words, but grew silent as they realized that for the men who played the music was a sacrament soon to be consummated by death. The serene strains of the hymn and the frantic cries of the dying blended in a symphony of sorrow.

Led by the green light, under the light of the stars, the boats drew away, and the bow, then the quarter, then the stacks and at last the stern of the marvel-ship of a few days before, passed beneath the waters. The great force of the ship's sinking was unaided by any violence of the elements, and the suction, not so great as had been feared, rocked but mildly the group of boats now a quarter of a mile distant from it.

Sixteen boats were in the forlorn procession which entered on the terrible hours of rowing, drifting and suspense. Women wept for lost husbands and sons. Sailors sobbed for the ship which had been their pride. Men choked back tears and sought to comfort the widowed. Perhaps, they said, other boats might have put off in another direction toward the last. They strove, though none too sure themselves, to convince the women of the certainty that a rescue ship would appear.

Early dawn brought no ship, but not long after 5 A.M. the Carpathia, far out of her path and making eighteen knots instead of her wonted fifteen, showed her single red and black smokestack upon the horizon. In the joy of that moment, the heaviest griefs were forgotten.

Soon afterward, Captain Rostrom and Chief Steward Hughes were welcoming the chilled and bedraggled arrivals over the Carpathia's side.

Terrible as were the San Francisco, Slocum and Iroquois disasters, they shrink to local events in comparison to this world-catastrophe.

The world's annals have provided few more intense and dramatic moments than when all that was left of the great company that sailed so gayly on the Titanic appeared on the Cunard pier. No hint of the story of their miseries and of their sufferings after the Titanic foundered had come from the sea. It was not known for certain whether some who had been given up for dead might appear miraculously on the gangplank. There were scores of people, among them men and women whose names are familiar the country over, who waited in the most intense suspense while the Cunarder with her sad cargo made her way slowly up the Hudson, passed the great ships in dock, whose flags showed dimly at half staff in the bars of river light. There were some of these who did not dare to give up all hope, who lingered still a prey to the most dreadful uncertainty, who refused to believe the cruel list of those that were saved and thought that there might all appear for them some loved face. But nearly all of these were disappointed and turned away with looks that no man who saw the arrival of the Carpathia will ever forget.

The tragedy of the Titanic was written on the faces of nearly all of her survivors. Some, it is true, who were saved with their families could not repress the joy and thankfulness that filled their hearts, but they were very few compared to the number of the rescued. These others bore the impress of their time of darkness when their people passed in an accident that seemed like an insane vision of the night. Their faces were swollen with weeping.

The unhappy company so marvelously torn from the grip of the sea was received solemnly and with remarkable quiet by the crowd which gathered near the Cunard piers and by the few hundreds that penetrated by right of relation or friendship or merciful business to the interior of the pier. There was no cheering, no upraising of voices in salute of the living, for the thought of the dead was in the minds of all onlookers. The depression of death was oppressive on the spirit of the waiting men and women. Those who found their gladdest hopes realized and looked through the press to make out the well-known faces of husbands and fathers and sisters and wives could not conceal their tremendous elation, their thankfulness that all suspense and disheartening conjecture was over. But they greeted their rescued ones quietly for the most part.

Simon Senecal, a merchant in Montreal, who was a passenger on the Carpathia, in telling of the Titanic disaster, said:

"After rescuing the boatloads of women we sighted a liferaft on which were about twenty-four persons. One-half of these were dead. One of the Carpathia boats went to the raft and took the live men off, leaving the dead. The water was thick with bodies. Why, the crew of the Carpathia in rescuing had trouble in avoiding the bodies as they floated about in the water.

"I know of seven bodies which were buried by the crew of the Carpathia after the rescue. If there were any other bodies buried I do not know."

| TRYING TO SMASH SPEED RECORD |

J.M. Moody, a quartermaster of the Titanic and helmsman on the night of the disaster, said the ship was making twenty-one knots an hour, and the officers were striving to live up to the orders to smash a record.

"It was close to midnight," said Moody, "and I was on the bridge with the second officer, who was in command. Suddenly he shouted, 'Port your helm!' I did so, but it was too late. We struck the submerged portion of the iceberg."

"It was close to midnight," said Moody, "and I was on the bridge with the second officer, who was in command. Suddenly he shouted, 'Port your helm!' I did so, but it was too late. We struck the submerged portion of the iceberg."

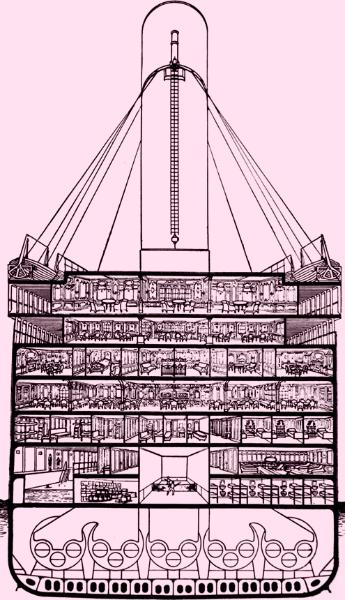

| SECTIONAL VIEW OF THE TITANIC. |